In many spiritual practices, dualities such as the Goddess and the God, Shakti and Shiva, or Yin and Yang, are central concepts. These opposites often represent the divine feminine and divine masculine, playing significant roles in shaping Pagan practices and beliefs. But do these dualities serve us, or do they limit the breadth of our practices? Is gender necessary for our spiritual workings? And does the tension of polarity really enhance our magic—especially in practices like sex magic? Perhaps not.

To begin with, it’s important to distinguish between sex and gender. Sex refers to biological differences used for reproduction, like the union of pollen and pistil or sperm and egg. Sexual reproduction necessitates the coming together of two different gene-carrying parts, and these differences give rise to hormones like estrogen and testosterone, which shape how a person develops.

However, gender is far more complex. It refers to a socially constructed identity, a learned performance often tied to biological sex, though this performance can vary by time and culture. Gender can also be an internal, personal experience, whether or not it aligns with the sex assigned at birth. Many are now embracing the understanding that not everyone fits neatly into binary categories of male or female.

For most people, duality is a familiar framework for understanding the world. Throughout history, thinkers like Plato and Descartes taught that the world can be divided into opposites—night and day, good and bad, mind over matter. Yet, some cultures, such as the Celts and the Chinese, embraced different ways of dividing the world. The Celts favored triads, such as land, sea, and sky, while the Chinese considered four to be a lucky number. Clearly, the importance of dualities can vary, and not all systems reduce the world to just two forces.

One duality commonly found in modern Paganism is the tension between the esoteric and the animist. Esoteric practices view symbols and objects as representations of deeper meanings. This is rooted in traditions like Ancient Egyptian magic, the Qabalah, alchemy, and astrology. These systems rely heavily on symbolism to invoke meaning, with male and female energies often represented through the sun and moon, athame and chalice, or the Goddess and the God. In such esoteric traditions, magic is often believed to be activated by bringing together these opposite forces.

While this approach works for many, it’s worth questioning how necessary it is to assign gender to symbols. For example, when we associate fire and air with masculinity, and water and earth with femininity, what do we really mean? Does gendering these elements expand our understanding, or does it constrain them within a narrow framework? Do we need fixed gender roles for deities, or can we explore a more fluid understanding of the divine? Ancient gods and goddesses were often much more fluid in their gender representations than modern interpretations suggest.

Consider Ares, the God of war, and Aphrodite, the Goddess of love. Do such rigid associations encourage people to adhere to societal expectations of masculinity and femininity? Can a warrior not possess love, and a lover not show strength? The question of gendering the divine remains open to interpretation.

If polarity is essential in our magical workings, are male and female the only meaningful polarities? Certainly, when it comes to reproduction, male and female are necessary. But when we look at more abstract creations, the inner and outer, self and other, may prove to be more profound polarities. As some thinkers, like Yvonne Aburrow, have suggested, the polarity between self and other is a critical dynamic in the world of magic.

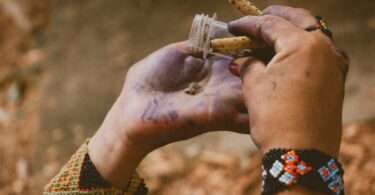

Some magicians, such as Patricia MacCormack, argue that magic thrives when we move beyond dualities, entering into liminal, non-binary spaces. These spaces break down boundaries and challenge preconceived notions of gender and identity. Likewise, Austin Osman Spare believed that dualism limits creative thought. Animist magic, in particular, works with the inherent qualities of objects, not just the symbolic meanings we’ve attributed to them over time.

In practices like sex magic, the physical act may require arousal, but it doesn’t necessarily require two specific sexes or genitalia. Sex magic is about more than just orgasm; it’s a creative force that can take many forms. Similarly, it doesn’t need to follow conventional gender roles to be effective.

The question arises: Is it even feminist to gender our magical practices? In the mid-20th century, figures like Gerald Gardner took steps to elevate the importance of the Goddess alongside the God, challenging the patriarchal structures of traditional religions. In the 1970s, the feminist movement embraced the concept of a powerful, divine feminine as transformative. But in contemporary times, how relevant is this gendered approach?

To create inclusive magical practices, we need to be open to non-binary, queer, and gender non-conforming people. The practice should welcome everyone, regardless of gender, and focus on inclusivity. For instance, is the celebration of Beltane really about the union of the Goddess and the God, or can it be reframed as a celebration of abundance, delight, and desire in all its forms? When we focus on the actual seasons and natural cycles, we may move away from rigid gender roles, offering a space for all to find resonance.

Ultimately, our souls transcend gender. The aim of systems like the Qabalah, yin and yang, or the tarot is not to define our “essential” masculinity or femininity, but to seek balance, unity, and transcendence. The tarot’s Major Arcana, for example, contains both masculine and feminine archetypes, but the Fool, beginning the journey, is androgynous, and the World, representing completion, encompasses all genders.

At times, we gender things to make them easier to understand, to fit them into a structure that aligns with our perceptions of the world. Gendered metaphors can be useful, but we must be mindful of their limitations. There may be times when gender can help deepen our practices, but we must ask ourselves: Does assigning gender enhance or limit our magical work?